Lansdowne 2.0: A Look at One of Ottawa’s Most Significant City-Building Decisions

I want to begin by thanking everyone who has taken the time to reach out to me about Lansdowne 2.0. This project is deeply personal and emotional for many, not just in our community, but across the City of Ottawa. With so many conflicting narratives surrounding the proposals, I hope you’ll forgive the length of this post. I want to take the time to share my thinking and the extensive work I’ve done to understand the full scope and nuance of this initiative.

This is likely one of the most consequential decisions that City Council will face this term. I’ve spent countless hours reviewing reports, financial statements, and news articles, and listening to perspectives from all sides of the debate. My goal has always been to approach this issue with transparency, diligence, and a commitment to the long-term interests of our city.

Important Update – November 6, 2025

The City Manager has shared the below memo speaking to some of the questions received about the project. I am sharing that memo below.

Important Update – October 29, 2025

The Lansdowne 2.0 plans have been evolving from a decision made several years ago, when the new arena size was selected in spring 2022. Recently, concerns about that size have been raised by the PWHL, residents, and Councillors. In response, Council requested that staff outline what would be required, and the associated costs, to revisit that decision.

The City Manager has provided a memo to Council with those answers, which I am sharing in full below, to ensure complete transparency.

As further background, the PWHL is not a member of OSEG. As a renter of the site, their interactions/comments on the redevelopment have primarily been with OSEG directly, beyond what they shared during delegations (which I speak to further below). OSEG is responsible for leasing Lansdowne and managing site operations. Typically, lease negotiations, past and present, are not made public. However, due to conflicting messages currently circulating, OSEG has provided a letter to the City Manager detailing the full timeline and nature of their communications with the PWHL.

That letter was shared with Councillors, and I have included it in full, attached to the memo.

Arena Sizing and Timelines

Regarding the PWHL and the Charge, let me be clear that I am huge fan and I absolutely don’t want to see them leave. What I struggle with however, is adding upwards of $100 million to the project, with such a cloud hanging over their 11th hour concerns, raised only a week before the final vote. If they signed a contract similar to OSEG’s, committing to remain in the arena and agreeing to a penalty equal to the upgraded costs, that would at least be a starting point. But when I heard them speak at committee about how their American arenas seat between 12,000 and 18,000, and how they look forward to growing here in Ottawa (which I would truly love to see), it became clear that Lansdowne simply cannot accommodate anything of that scale. That is what the CTC and the future LeBreton arena are designed for. Lansdowne is meant to be a mid-size arena, to fill the gap between the NAC’s roughly 2,000 seats and the CTC’s 18,000 capacity.

This need for a mid-size arena is what drove the selection of this size. Coincidentally, it is also one of the reasons the LeBreton site will be smaller than the CTC. Beyond supporting current tenants, Lansdowne aims to attract new, world-class events that are currently bypassing Ottawa. Curling was specifically mentioned in this context. The Men’s World Championships made it clear they wouldn’t return after their last visit to TD Place, where leaks nearly forced them to cancel the tournament. Events like Cirque du Soleil and Curling Canada’s Brier Cup are looking for venues in the 5,000+ seat range. The Brier Cup, for example, has used venues like Mary Brown’s Centre in St. John’s (7,000 capacity) and Prospera Place in Kelowna (6,000 capacity). These events often cannot afford to rent or fill larger venues. While scaling up may seem like a simple decision, an 8,000 to 11,000-seat facility is financially out of reach for many of the renters that would be targeted.

When Cirque du Soleil came to Ottawa with their OVO show, they reduced seating at the CTC to around 4,600 and took a loss on rental fees. Their Echo show played in Gatineau at Place des Festivals Zibi, with a capacity of about 2,500 to 2,600. While an organization like Cirque may be able to absorb losses and charge ticket prices north of $150-300, that is not feasible for smaller or more targeted events like curling.

The new arena will be competing with other venues for renters, which is why the redevelopment plans have been carefully designed to minimize that impact. They specifically target Ottawa’s missing middle venue size, a gap in the city’s current offerings. Importantly, the size of the arena is not new information. It was first announced in April 2022, a full 16 months before the PWHL revealed its plans to come to Ottawa.

Similarly, the vote taking place in November 2025 does not introduce any new or unexpected details regarding the arena’s size, layout, or intended use. City Council already approved moving forward with the tendering process back in April 2024. At that time, the full designs were made public, as potential contractors needed to know exactly what they were bidding on. The current vote is simply to authorize staff to sign the construction contracts.

In short, for those who have been following the Lansdowne 2.0 file, this report contains very little new information, aside from the announcement of the selected contractor and confirmation of the fixed-price construction costs, which I detail below.

Financial Clarity: From Estimates to Actuals

In October, the financial reports for Lansdowne 2.0 were released (https://pub-ottawa.escribemeetings.com/Meeting.aspx?Id=1f5aeaf9-996c-47ca-a637-ef214cf8be9a&Agenda=Agenda&lang=English). These documents address one of the key financial questions that has shaped much of the public debate. Until now, City staff had been working with “Class C” estimates: early-stage projections that carry a wide margin of uncertainty. The original estimate for construction costs was $419 million (Page 9 – https://pub-ottawa.escribemeetings.com/filestream.ashx?DocumentId=268086).

When the City’s Auditor General completed her audit of the project, (https://www.oagottawa.ca/media/1yhp51e3/final_lansdowne_2-0_sprint_1audit_report_english_final-ua.pdf) she found that:

The due diligence process demonstrated a significant effort to engage sufficient and appropriate expertise, both internal and external to the City, to validate significant financial assumptions and projections for Lansdowne 2.0. Our work confirmed that all significant financial assumptions embedded in the financial projections were validated by external or internal9 subject matter experts with the necessary qualifications and expertise to provide such input. These experts contributed in various capacities, including the development of proformas, validation of projections and provision of informative market analyses. We appreciate that several of the components of the financial projections were updated to reflect the results of those due diligence activities.

(Page 9 “Conclusion” at previous link)

However, she cautioned that some of the construction estimates might be optimistic due to the inherent risks of delayed timelines and rising costs. Her audit suggested that costs could be understated by as much as $74.3 million (page 10 of her https://www.oagottawa.ca/media/1yhp51e3/final_lansdowne_2-0_sprint_1audit_report_english_final-ua.pdf). In response, staff prudently increased the buffer to account for this risk, an understandable move that nonetheless raised concerns and was widely cited by critics.

Now, with the new report, we have the results of actual fixed-price tender bids from multiple contractors. These new “Class A” financials reflect the real, confirmed construction costs of the project. The total required budget, including a buffer, is $418.8 million (page 102 – https://pub-ottawa.escribemeetings.com/filestream.ashx?DocumentId=268086), coming in $280,000 (page 104 – https://pub-ottawa.escribemeetings.com/filestream.ashx?DocumentId=268086) below the original estimate.

This level of accuracy is remarkable and provides a much clearer financial picture for Council and residents alike. We are no longer required to rely on speculative numbers, nor increase buffers based on unknowns. It is also reassuring to see that staff’s original estimates were ultimately so spot on.

Capital Costs

The total capital cost for the construction project is $418.82 million (page 102 – https://pub-ottawa.escribemeetings.com/filestream.ashx?DocumentId=268086. This final costing includes EBC Inc’s (the company with the successful bid) fixed price for the construction of the event centre, new north side stands, and public realm enhancements. It also includes the estimated costs for the grand entrance and new event centre parking garage to be delivered by a second company, Mirabella Development Corporation. Additionally, it includes just under $22 million of Council-approved spending to date on project management, site plan development, detailed design, procurement, financial due diligence and legal amendments to the partnership agreements, as well as all the remaining costs the City will incur to implement the project.

| Lansdowne 2.0 – Event Centre and North Side Stands Budget | |

| Description | Amount ($million) |

| Event Centre | $ 176.82 |

| North Side Stands | $ 119.38 |

| Grand Entrance (Developer delivered) | $ 5.29 |

| Parking for Event Centre (Developer delivered) | $ 3.50 |

| Site development: services and utilities | $ 0.50

|

| Subtotal Construction Costs | $ 305.50 |

| Concept Development and Planning | $ 7.50 |

| Permits and Fees | $ 2.97 |

| Design and Construction Consultants | $ 32.94 |

| Contract Administration Costs | $ 9.17 |

| Business and Other Costs | $ 23.77 |

| Contingency | $ 36.10 |

| Escalation | $ 0.88

|

| Total estimated cost | $ 418.82 |

A New Financial Model

While the City owns and is responsible for the site, it must also ensure that any redevelopment plans are fiscally responsible. Under Lansdowne 1.0, OSEG payments were prioritized over the City. Many are surprised to learn that Lansdowne 1.0 has not cost the City any money, it has been revenue-neutral for taxpayers. All losses were borne entirely by Ottawa Sports and Entertainment Group, not the City.

However, this arrangement also meant that the City did not receive any revenue. That’s why Lansdowne 1.0 didn’t cost the City money, but also didn’t generate any revenue. From a taxpayer’s perspective, it was a successful model in terms of risk mitigation, but not revenue generation.

Under Lansdowne 2.0, that changes. Ottawa would see direct and increased revenue from property taxes on the redeveloped site, a ticket surcharge, immediate revenue from the sale of air rights for residential towers, and a restructured waterfall agreement. This new agreement ensures that both the City and OSEG are repaid their equity contributions at the same time.

- https://ottawa.ca/en/city-hall/public-engagement/public-engagement-project-search/lansdowne-20

- https://pub-ottawa.escribemeetings.com/Meeting.aspx?Id=1f5aeaf9-996c-47ca-a637-ef214cf8be9a&Agenda=Agenda&lang=English&Item=24&Tab=attachments)

As detailed in the link above, OSEG has agreed to pay $500,000 annually in rent for both the stadium and event centre. Additionally, a ticket surcharge will generate $300,000 annually for the first 10 years, increasing to $1.50 per ticket and rising by $0.25 every five years. This surcharge alone is expected to provide an average of $700,000 annually.

Unlike the previous model with Lansdowne 1.0, these revenue streams are reliable and predictable. The financial forecasting has been fully audited by Ernst & Young LLP (EY), with their review including the complete analysis of the 52-year development pro forma, financial feasibility, and risk assessment prepared by City staff. While the upfront costs are high, the remaining amount is debt-financed and will be repaid by these new revenues.

Clarifying the Real Cost to Taxpayers

A common misconception is that Lansdowne 2.0 will cost taxpayers the full $418.8 million. In reality, due to the fixed revenue streams generated by the redevelopment above, the immediate cost to taxpayers is approximately $130 million. However, even that figure comes with important caveats. These financial plans are intentionally conservative, focusing only on direct and “fixed” revenue streams. Given the scale and importance of this project, it was prudent for staff to take a cautious approach in their financial modelling. However, it is equally important to recognize that other revenue sources do exist.

The redevelopment will also generate significant indirect economic benefits and revenues:

- The project will trigger over $950 million in capital investment in Ottawa.

- Lansdowne 2.0 will create nearly 500 new jobs annually during construction and more than 400 permanent, full-time jobs once completed.

- A redeveloped Lansdowne will contribute $590 million in GDP over the next decade and $89 million annually in visitor spending once fully operational.

- A modernized Lansdowne will become a more attractive and competitive destination for major events, with a projected 22 percent increase in ticketed attendees and $8 million in new out-of-town spending annually.

The City report on the Economic Impact of the Lansdowne 2.0 Redevelopment can be found here:

- https://pub-ottawa.escribemeetings.com/filestream.ashx?DocumentId=268076, and

- https://pub-ottawa.escribemeetings.com/filestream.ashx?DocumentId=268077)

While these indirect revenues are not included in the core financial model due to their speculative nature, they are still part of the broader conversation. Best practices in accounting rightly exclude them from fixed projections, but their impact on Ottawa’s economy and the project cannot simply be overlooked.

To better digest these numbers, the City has prepared a slide presentation that further details the numbers and presents them in a more user friendly way.

Debunking a Common Misconception

One of the most persistent misconceptions about Lansdowne 2.0 is that cancelling the project would free up $418 million for other City services or initiatives. This is unfortunately inaccurate and misrepresents the financial structure of the project.

Lansdowne 2.0 is only feasible because its upfront costs are directly tied to revenue streams generated by the redevelopment itself. These revenues would not exist without the project, meaning the funds cannot simply be redirected elsewhere. Cancelling the project would not create a windfall, it would eliminate both the costs and the dedicated revenues that make the project possible.

Moreover, there are significant and unavoidable costs associated with not moving forward. Without the project, no new revenue streams would be generated, and those costs would fall entirely on the tax base.

A Public Asset with a Public Responsibility

Unlike a private venue, Lansdowne Park belongs to the City of Ottawa. Whether Lansdowne 2.0 proceeds or not, that fact remains unchanged. We cannot simply walk away from this responsibility.

This model of publicly owned stadiums and arenas is not unique to Ottawa. Across Canada and the United States, cities own and operate major venues: Toronto’s BMO Field, Hamilton’s Tim Hortons Field, Regina’s Mosaic Stadium, Edmonton’s Rogers Place, Calgary’s (currently under construction, future home for the Flames) Scotia Place, Quebec City’s Videotron Centre, Laval’s Place Bell, the list goes on. Many CFL, NFL, NHL, NBA, and MLB stadiums follow this precedent.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BMO_Field,

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hamilton_Stadium,

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosaic_Stadium,

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rogers_Place,

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Place_Bell,

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scotia_Place,

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Videotron_Centre

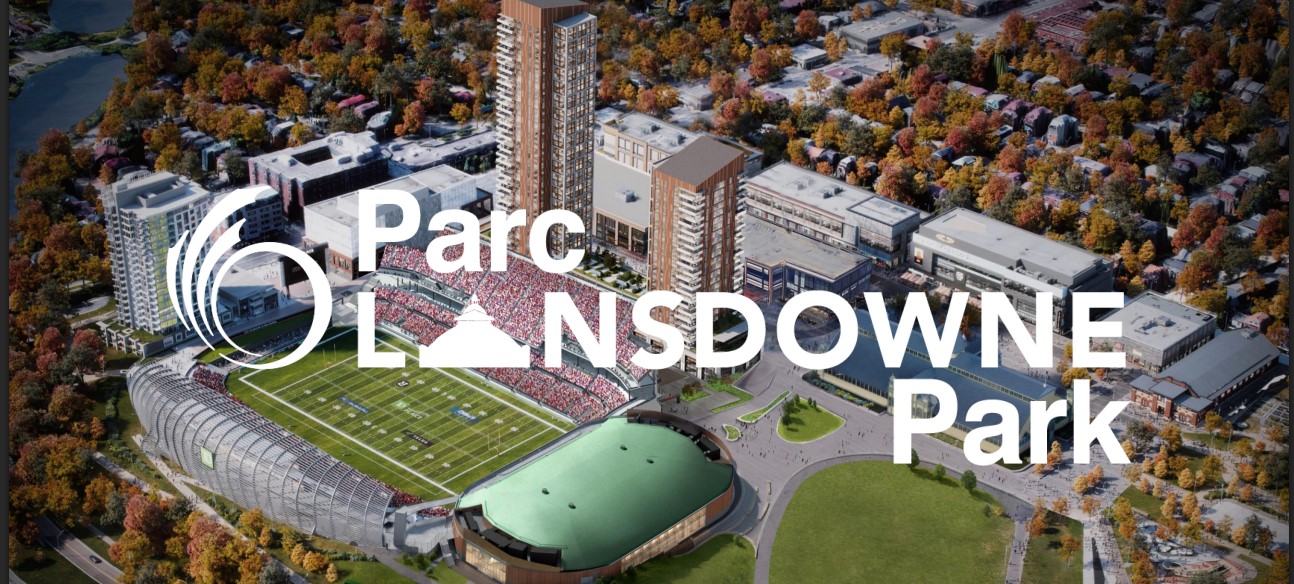

Lansdowne has been an iconic location in Ottawa for more than 175 years. It has served as a community gathering place and a vital public asset. Unfortunately, for decades, elected officials neglected it, allowing it to deteriorate into a giant parking lot with crumbling stands and aging infrastructure.

Lansdowne 1.0 marked a turning point. The southern half of the site was transformed, concrete and asphalt gave way to a great lawn and urban park where children play and world-class musicians perform. The condemned south side stands were replaced with a modern stadium that has hosted a Grey Cup, professional soccer, and an NHL Heritage Classic.

Lansdowne over the years.

New shops, restaurants, and attractions like the Lansdowne Farmers Market and Christmas Market and music festivals have animated the space, making it a destination for residents and visitors alike. Before the renovations, Lansdowne saw fewer than 250,000 visitors annually. Since then, it has welcomed more than 20 million people – over 4 million each year – from across the city and around the world.

There are now more than 4,000 full- and part-time jobs on the site, and the redevelopment has directly and indirectly generated tens of millions of dollars for the City of Ottawa.

Designing a Venue That Works

Concerns have been raised regarding the proposed arena size and roof design as part of the Lansdowne 2.0 redevelopment. The planned capacity is approximately 7,000 for concerts and 6,600 for hockey. This size was determined through consultation with experts in professional and amateur sports, as well as producers of major events, with the goal of serving the widest possible range of uses. A medium-sized venue of this nature is considered ideal for maximizing usage and attracting a diverse mix of sports and entertainment programming. While the Canadian Tire Centre offers a large-scale option, and there are smaller venues across the city, Lansdowne presented an opportunity to fill that much needed middle ground. The mid-sized venue is a space that’s in high demand and currently completely missing in Ottawa’s event landscape.

Throughout the process leading up to this October, every single player, manger, coach or representative, speaking on behalf of the sports teams who call Lansdowne home were unambiguous in their support for the project. During public Committee meetings, representatives from OSEG and the various other sports teams, including players and management, spoke in support of the redevelopment. Their feedback focused not on the proposed size, but on the deteriorating condition of the existing facility. Issues such as inadequate locker rooms, poor ventilation, and mold were repeatedly cited as barriers to continued use. All representatives were clear that remaining in the current arena would not be viable.

Following the release of the final Lansdowne 2.0 reports, the PWHL has raised concerns about the proposed arena size (https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/pwhl-ottawa-arena-lansdowne-park-9.6952279). Their comments come as a surprise this late in the process, it highlights an important conversation, and the need to balance the long-term viability of the existing tenants, with the business case centered around the market gap that a mid-size arena fills.

As we move toward Committee and Council discussions, it will be helpful to better understand these perspectives, and I look forward to hearing from OSEG, the project team, and Ottawa PWHL franchise at Committee. These conversations will ensure that decisions are informed by a wide range of voices and reflect the best possible outcome for this project.

As with any major civic project, ongoing feedback and public engagement may lead to refinements in the design, including elements such as capacity and roof structure. These aspects will continue to be reviewed to ensure the final plan meets the needs of both users and the broader community.

Transportation Access

Lansdowne is both a City-owned and City-wide asset, attracting visitors from every corner of our nation’s capital. Transportation access has rightly been a major focus of discussion, and for good reason: the long-term success of this site depends not only on the investments proposed through Lansdowne 2.0 but also on our ability to get there. For many residents living outside the downtown core, and certainly for Ward 2 residents, traveling to Lansdowne currently requires driving and finding parking, limiting their ability to easily access the site.

While peak demand during individual events is anticipated to remain stable, the addition of a modern Event Centre, a new North Side Stands, and the improvements proposed through 2.0, would result in more frequent events and increased activity at Lansdowne, leading to a higher overall volume of trips to the area over time. Right now, OSEG covers the cost for free transit for all ticketholders before and after events, including routes 6, 7, and the 450-series special event shuttles (an approach that is the first of its kind in North America for a large mixed-use entertainment district). If Lansdowne 2.0 moves ahead, we need to support this work with long term, viable transportation options that allow users of the site to access it easily. Not just for large events, but throughout the week as one of the premier entertainment districts in our City.

Consultation and planning on the Bank Street Active Transportation and Transit Priority Feasibility Study (https://engage.ottawa.ca/bank-street-active-transportation-and-transit-priority-feasibility-study), is well underway. The feasibility study covers Bank street from the 417 down to the Rideau Canal, designating this stretch as a Mainstreet and Transit Priority Corridor, and examining options to improve transit along what is truly a key corridor and one of the main routes to access Lansdowne. This is an important step toward identifying infrastructure improvements; however, infrastructure planning alone does not guarantee meaningful transit access, and there remains an urgent need to commit to actual service delivery; including dedicated routes and reliable scheduling. These elements are critical to the success of the site and to the experience of residents and visitors alike.

The Cost of Doing Nothing

No matter what happens, the arena is nearing the end of its life cycle, and the north side stands are not compliant with modern accessibility standards. If we do nothing, we will still face the cost of replacing or repairing these facilities, but without the benefit of a broader plan or revenue strategy to support it. This is not opinion, this was the unquestionable finding from over a dozen different engineering assessments.

To speak bluntly, the north-side stands and arena are beyond repair: they leak, the washrooms are unusable and multiple event organizers—including the World Curling Championships, Cirque du Soleil, and the Ottawa Charge, have told us they will not return until the facilities are modernized. A substantial factor in Lansdowne’s success is its ability to attract world-class events, and it has become clear that the current infrastructure has not only lost its competitive edge, but event organizers are now actively avoiding it.

The Reality of Cancellation or Delay

If Lansdowne 2.0 were cancelled, the cost of doing nothing would be extremely high. Ottawa has a history of deferring infrastructure investments, only to pay more later. The preliminary cost of maintaining and eventually demolishing the current facility originally was pegged around $400 million. That figure does not include any improvements or future plans. Any future public space would be fully taxpayer-funded, with no associated revenue streams. As reported, and confirmed by Ottawa’s Auditor General.

- https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/lansdowne-park-td-place-ottawa-update-construction-9.6947572

- https://www.oagottawa.ca/media/1yhp51e3/final_lansdowne_2-0_sprint_1audit_report_english_final-ua.pdf – page 4

Using the financials for the redevelopment costs today, staff were able to provide a high-level estimate for delaying the project. If Ottawa were to wait another decade, the net cost to taxpayers would be between $597 million and $752 million. Unlike with the current proposal, this amount would almost assuredly be borne entirely by taxpayers, as it is all but guaranteed that OSEG would walk away from the partnership.

This is not hypothetical. Representatives and players from PWHL, OSEG, and other users have made it clear that their teams cannot remain in the current crumbling arena. Again, their concerns include stagnant water, mold, leaking roofs, and inadequate locker rooms (https://www.youtube.com/live/vpUjjdm9brA?si=XNcclI2V04h7fHQG&t=9522).

If they leave Ottawa, they will not return. Staff have been clear: maintaining aging infrastructure, losing tenants and revenues, and eventually paying demolition costs would result in a far higher cost to taxpayers than what is proposed under Lansdowne 2.0.

Final Thoughts

I share this background because I want to be transparent about my own thinking and concerns. In my looking at the file, I have wanted to hear all sides of the issue, to strip away rhetoric or political ideology, and look at what are the facts of the matter. While some have suggested that rejecting or delaying Lansdowne 2.0 would come without consequences, that is simply not the case.

The City of Ottawa owns Lansdowne, a decision made 175 years ago. Whether or not we would make the same decision today is not the question before us. If Lansdowne 2.0 were to fail, we must be honest about the implications. Beyond the loss of sports teams, farmers’ and Christmas markets, concerts, and other events, there would be a significant financial cost, and there are currently no plans or means to cover it.

We know that the current conditions and the existing arrangement with OSEG are not sustainable. If the City were to mothball Lansdowne, we must be equally honest about what that would mean financially and operationally. Realistically, either those costs come from taxpayers, or the City has to look to other options to defray the costs. It has already been floated by some that should Lansdowne 2.0 fail, the City should simply sell off the land to whomever is willing to buy it. I can almost guarantee that whatever plans a developer would have for the site, it would not involve public parks, open air markets, and only two residential towers.

Looking Ahead

Lansdowne 2.0 is not just a construction project, it’s a city-building initiative. It’s about investing in a public asset, creating new revenue streams, supporting local jobs, and ensuring that Lansdowne continues to serve as a vibrant, inclusive space for generations to come.

I remain committed to reviewing every detail of this proposal and listening to the voices of our community. Thank you again for engaging in this important conversation.